Over the past 15 years I have seen several Middle East master plans designed and delivered – and then developed to maturity through their lifecycles.

Some have reached “critical mass”, where the required mix of residents, businesses, shops and other “activations” are in place. Others have stalled and are lifeless and commercially unsuccessful.

There can be any number of reasons for this, which in themselves are complex and might include competition, oversupply, design errors, and planning the wrong mix to begin with.

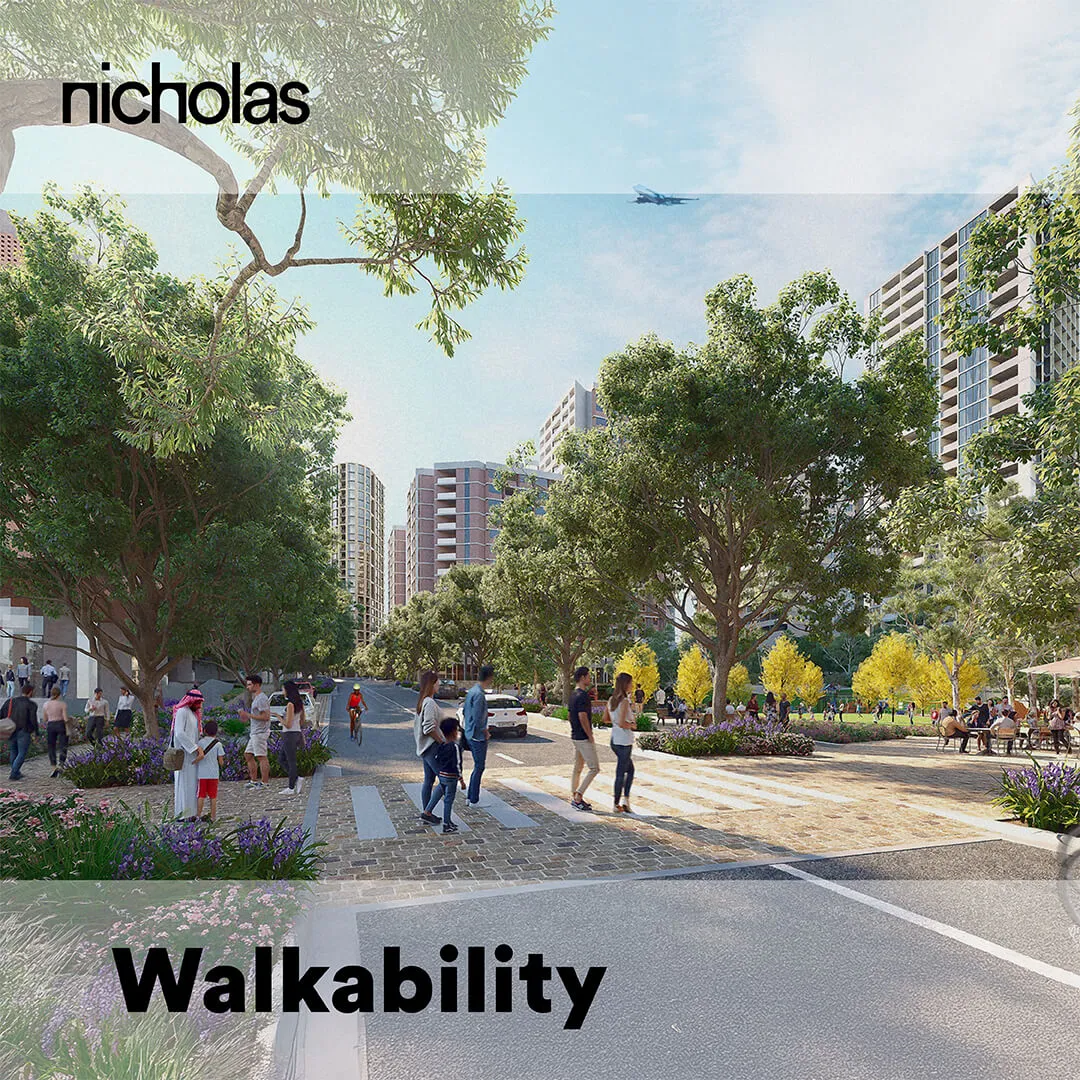

One element which underpins all successful planned communities and provides a clear measure of their economic and social success, is “walkability”. Put simply, the more pedestrian activity is prioritised within any development, the more prosperous it becomes.

In our context this means 5–7-minute walks between “destinations” in shaded (although not necessarily air-conditioned) environments – with protection provided by colonnades or other “designed” features, or appropriately selected trees.

The potential pitfall here is that the public realm aspect of urban design is often assigned to “siloed” transportation teams which – on auto-pilot – prioritise efficiency of the road network over almost everything else. Landscape architects are then invited to fill in the “gaps”.

This is even true of some giga-projects on the drawing board today.

For walkability to lead within the project, pedestrian (and cycling) infrastructure must be assigned greater hierarchical importance than roads. While the entire project must be comfortably and enjoyably walkable, it need not all be driveable – with cars separated or restricted to designated zones.

Although transport engineers may not wish to hear it, public realm design is most purposeful and effective when undertaken in a team environment that is architecturally led and with the stated goal of reducing car dependence.